Co-design with Malmö City Library

Creating a Vision for the Future of Libraries

About this project

Stakeholder: Malmö City Library

Duration: 8 weeks

Project Contributions: A group of 4 interaction design bachelor's students, including myself.

The design brief was to re-envision what a library is. There will always be a space for books in the library, but ideas about what a library is and could be will always be transformed according to the needs in society. The stakeholder wanted to transform the space according to the needs in society.

The purpose of this article is to look critically at our design process using participatory methods and how we handled challenges. We have actively involved the Malmö city library as stakeholders, demonstrating the definition of participatory design as “the direct involvement of non-designers in the co-design of the solutions that are sought” (Penin et al., 2019, p.3). I will reflect on our methods; such as a design game that we facilitated during workshops with library staff, and our process around the workshops.

Preparatory Research

Before conducting workshops with library staff, preparatory research was necessary to find design opportunities through problematization. “Prep research is less about finding answers and more about finding the right questions to ask in your research” (Stickdorn et al., 2018, p.7).

Our first step was desk research through academic journals, articles, blogs, and video materials to familiarize ourselves with librarian’s backgrounds, stereotypes, and how the concept is changing. Also, the introductory presentation from the Malmö city library framed the direction that the library seeks.

Our next step was visiting the library in person. I was pleasantly surprised that Malmö city library is already packed with resources to offer to patrons. However, there was still a lot of room for improvement.

The preparatory research helped us to shape relevant questions for the interviews.

Interviews

Our interview process is largely divided into two parts: library staff and patrons.

We interviewed 4 librarians & library assistants from different departments, such as Kanini & Balagan (children), lära och skapa (learning), literature, and a developer who was a former Krut (young adult) department. Through a total of 5 interviews, we investigated the library's hierarchy, backstage, and touch points between librarians and patrons.

Conducting interviews with the library staff helped us pivot our direction to more solid ground. We found out that the library is interested in cultural events and inviting different organizations to host these. In addition, the library staff expressed that the outdoor space of the library is not used often and could be utilized more. Our decisions were supported by developing our key insights, and we started to wonder what it means to mix cultures.

Furthermore, we were able to identify administrative and communicative challenges, and difficulties in the librarian's workflow. Unfortunately, some of these issues were too technical for us to tackle within a short amount of time, so we shifted our direction.

Challenge 1

Our interview questions did not stay according to plans, but instead, they evolved even in the middle of the interview and transformed depending on the information that we seek.

We had to be clear with our boundaries and not jump to the conclusion at the same time. For example, we failed to gain useful insights from the first few interviews because our questions were too vague, so we had to send additional questions by email. Also, it was challenging to keep interviews feel like a conversation rather than a Q&A. For natural conversation to be possible, one must be the primary talker, one to take notes, and another person to dive in from time to time to ask additional questions to deepen the conversation.

Often, I took on the role of driving the conversation, Shruti took notes, and Moawia and Carlo asked additional questions. Furthermore, Moawia and I took charge in reaching out to library staff and arranging meetings. Also, I have functioned as a primary point of contact, and library staffs found it convenient to have a consistent point of contact.

Shift in Directions

Based on our hypothesis, our original intention was to bridge the gap between librarians and patrons, and improve librarians’ work environment through a service design approach. However, after the interviews, we learned that we need a shift in direction due to technical limitations and deadlines.

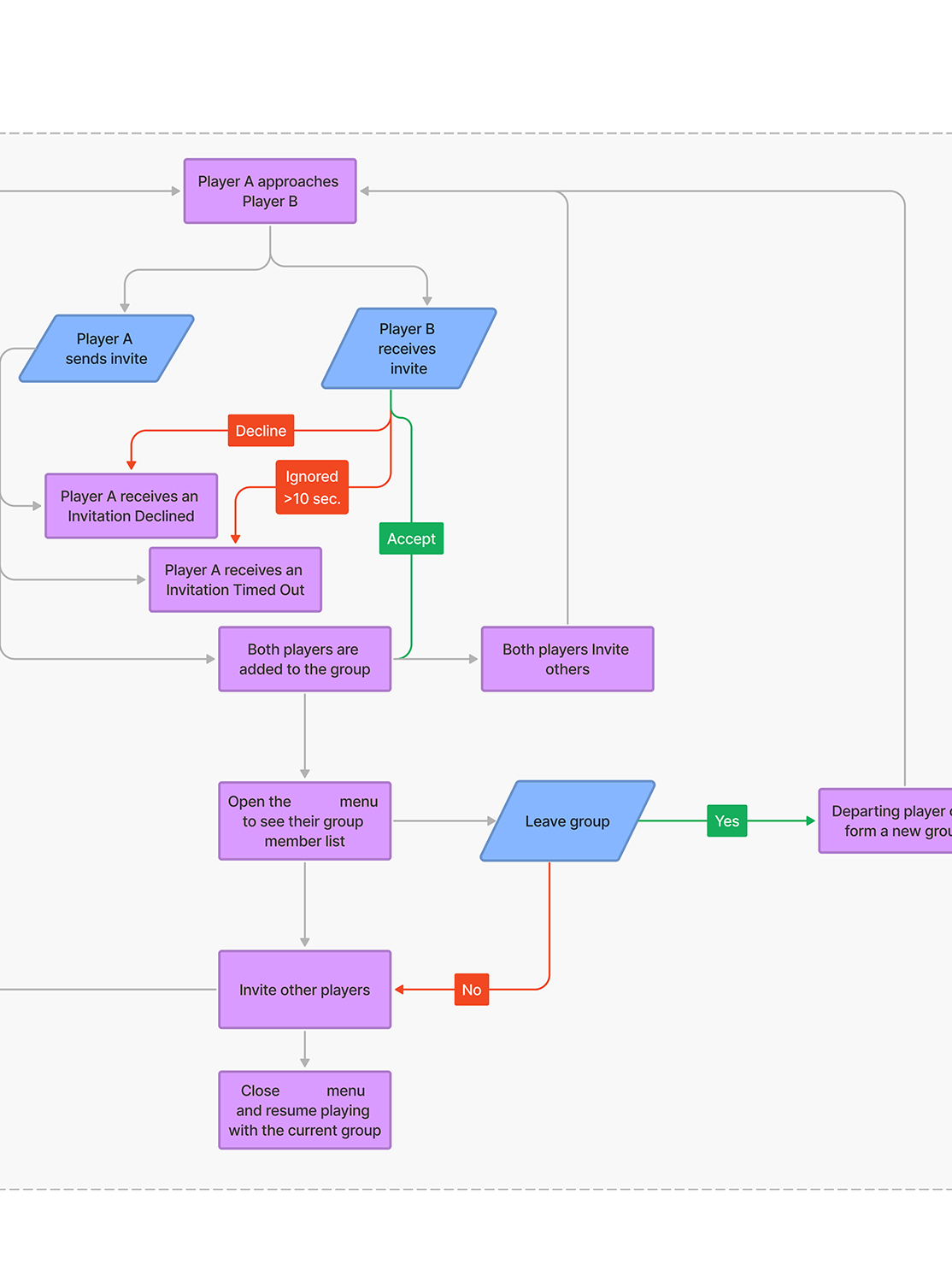

Our next consideration was taking the user-centered design approach, however, as we organized data and analyzed insights, we soon realized that the co-design method was crucial to our process. Unlike traditional user-centered design processes where “the user is a passive object of study”, the user plays “a large role in knowledge development, idea generation and concept development” in a co-design process (Sanders & Stappers, 2012, p. 24). We needed to facilitate a workshop to further engage stakeholders to reflect, explore, brainstorm, and ideate around a specific topic to empathize with the users and gain deeper understanding.

We have improved our process based on insights that are firmly grounded in real life, considering limitations, and actively communicating with teammates.

Participatory Observations

At this point, our definition of culture was still vague, so we set out to ask patrons regarding how they define cultures. We have participated at the language cafe as well as interviewing random patrons in the common library area. We tried to interview both Swedish locals and patrons from different backgrounds. However, we soon found it difficult to engage in deeper conversations with strangers and spark their interest.

Although not ideal, this led us to talk to our friends, family, and also among ourselves. We spent most of our lives being patrons instead of designers and we came from different cultures, which meant we fit our own target group. Unfortunately, this means objectivity of our insights are questionable, even though we tried our best to separate our identity as patrons and designers. Also, it is undeniable that we are not neutral even as designers. We have our own agenda to gain the kind of information we want to draw out of participants.

Co-design Workshop

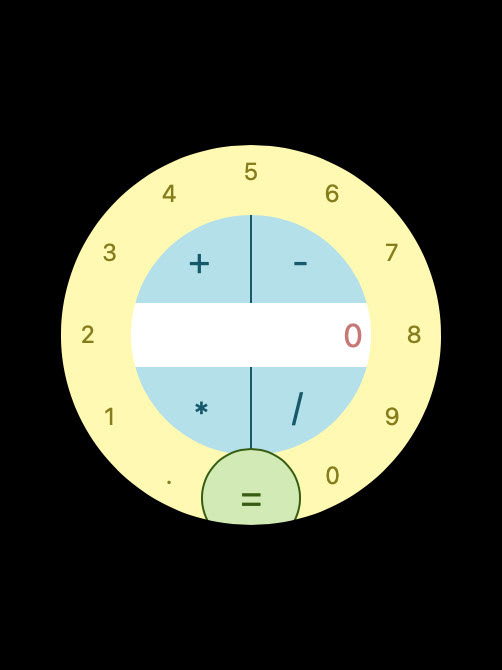

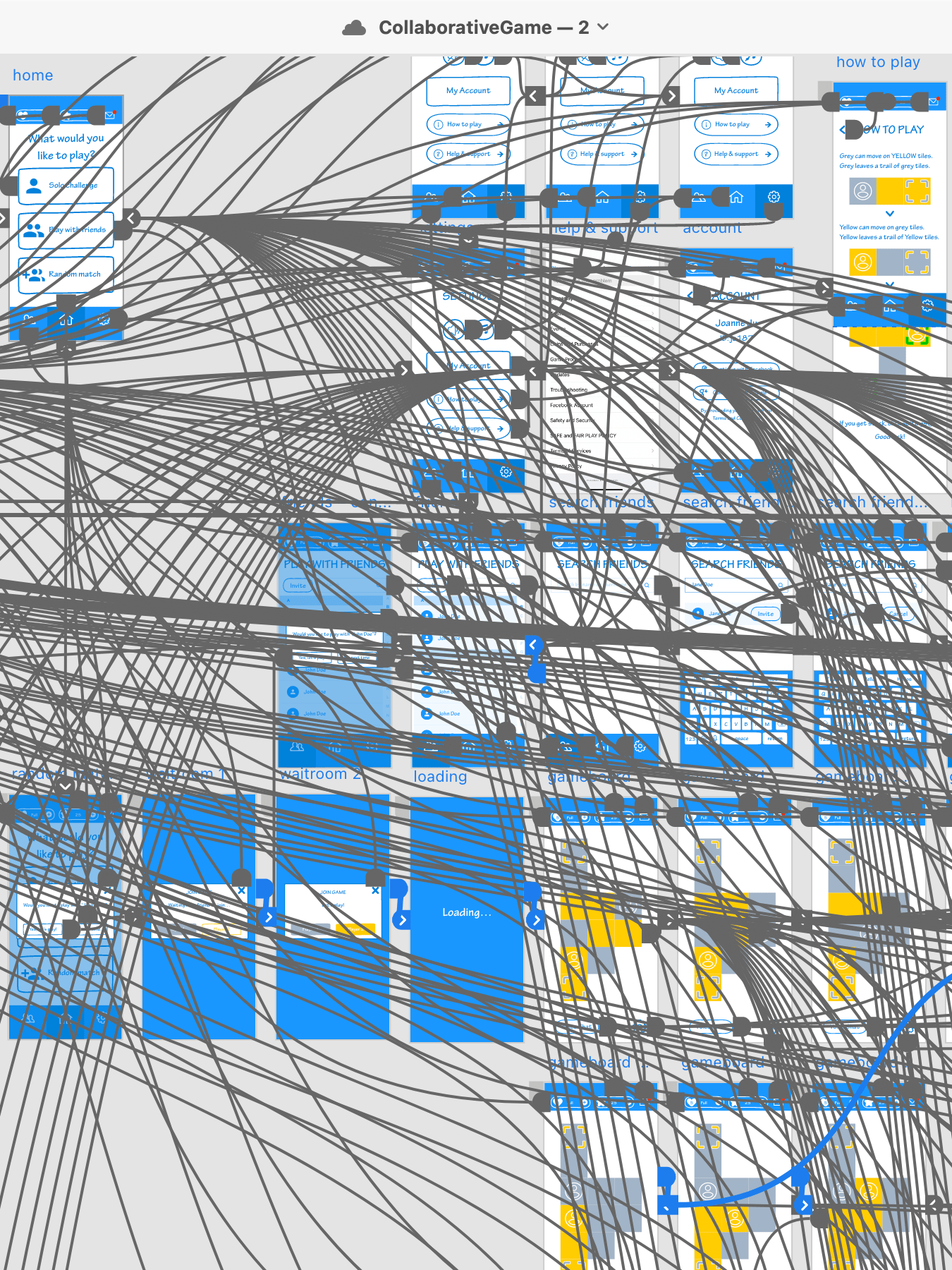

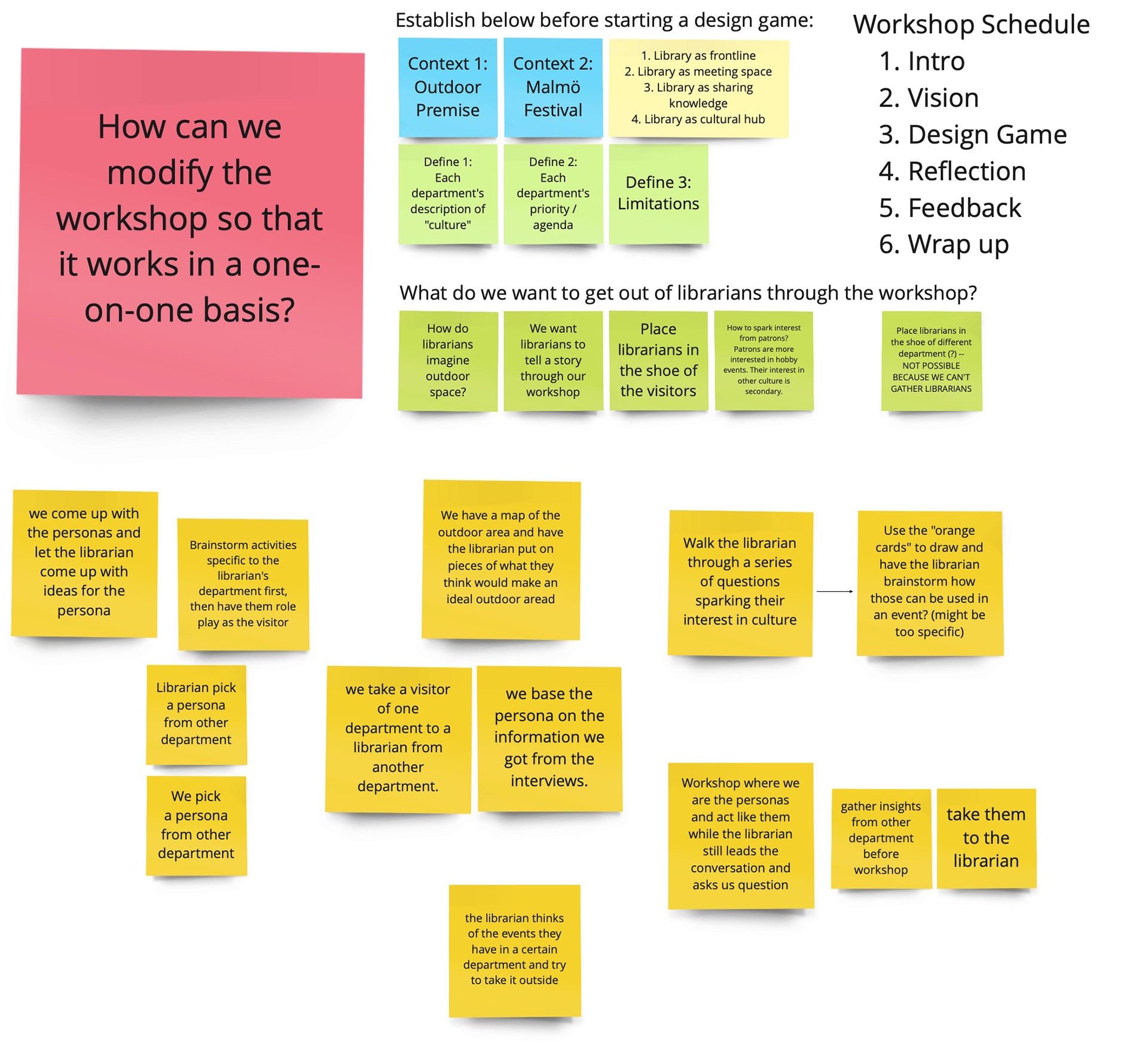

Our definition of culture was still vague, which served as the purpose of the workshop. This is where the active co-design methods take place. In general, codesign refers to inviting direct participation of non designers as designers, involving users in the design process (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). We wanted to find out how the library defines culture through planning and building their own ideal outdoor space.

We contacted 6 library staff, and only 3 were available. One of them was nice enough to grab an extra staff at the last minute, so we were able to facilitate 4 workshops total, forming a team of 2 designers and 1 library staff per session.

The workshops were facilitated as following:

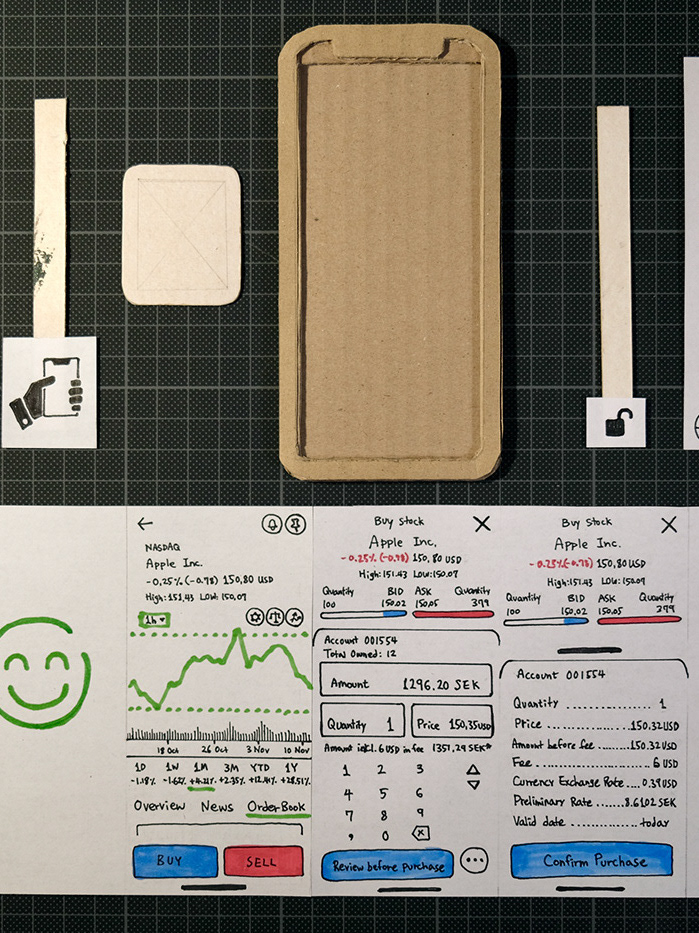

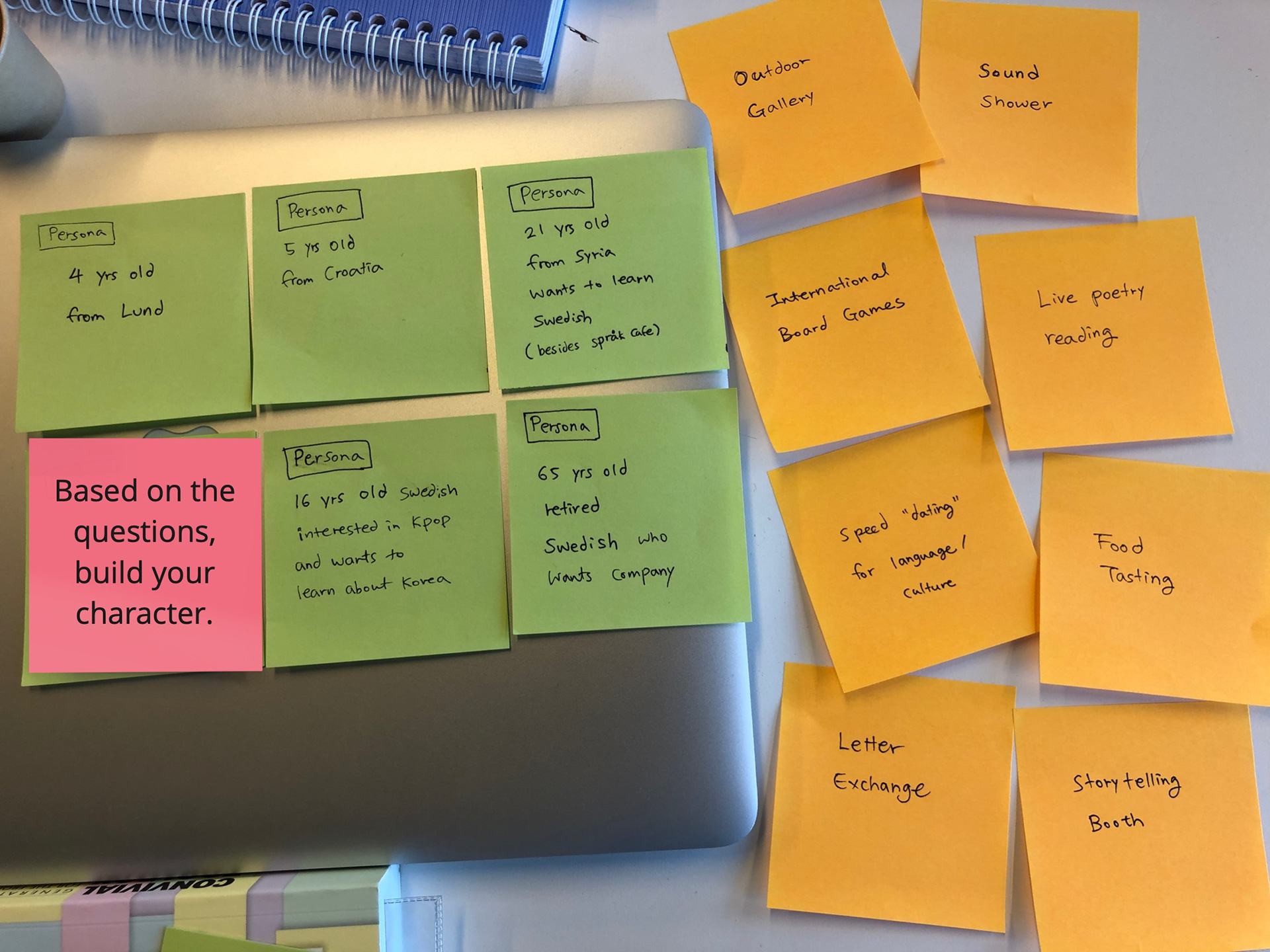

1. As representatives of each library department, library staff were asked to reflect on their idea of cultures, priorities, and what their average patrons look like.

2. Then they took on the persona of their average patrons to decorate their ideal outdoor space using the icons and sticky notes to explain their ideas. We found this to be essential because “one of the main reasons to create personas is to be able to have empathy with them, so you need to balance out the different factors and criteria you want to include in your personas with the need for authenticity” (Stickdorn et al., 2018, p.52).

3. Afterwards, our intention was for library staff to return to their role as library staff and comment on each other’s board on behalf of their department. Although we were unable to solve their communication problem with the management due to technical reasons, we still aimed to improve communication between departments.

Also, we had originally planned to conduct our workshop through online Zoom meetings for flexibility and efficiency, however, library staff’s digital competency was lower than expected, which pushed us to change our plan last minute to visit them in person.

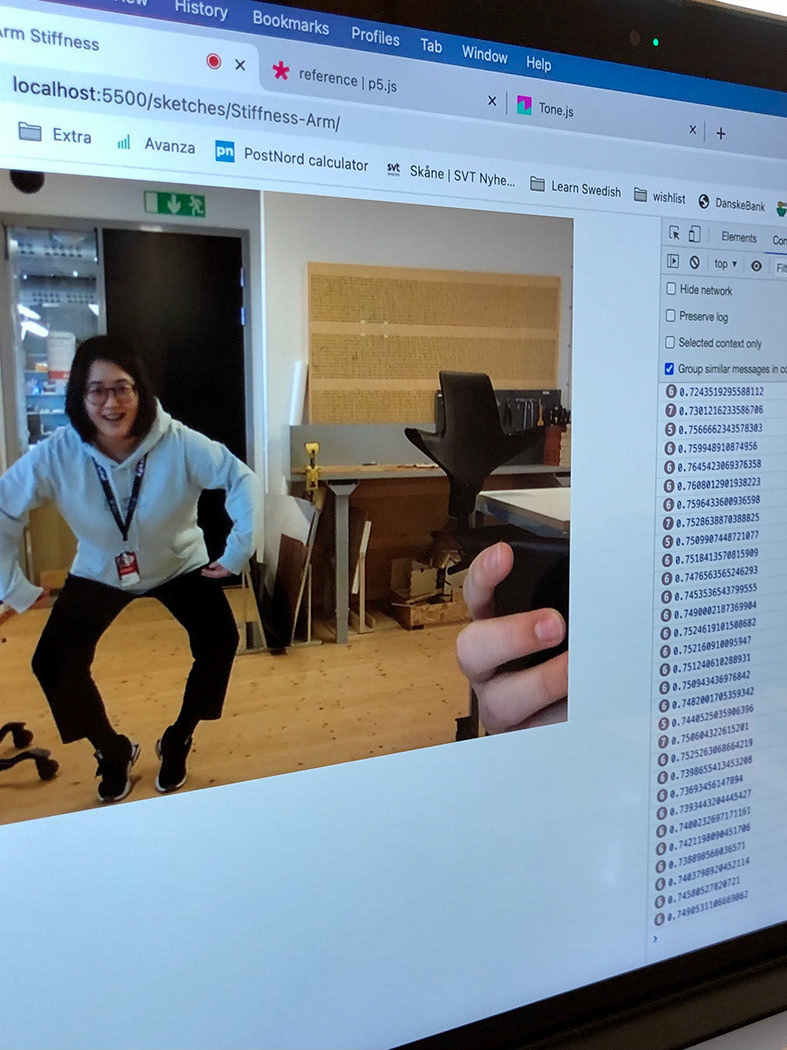

It was interesting to experiment with different facilitation styles. We got to compare our experiences between active and passive facilitation. For instance, we decorated the design game for 2 library staff on their behalf, actively asked questions, and constantly poked for more information. As for the other 2, the library staff decorated the board themselves at their own pace without additional questions until they were finished. Although we got solid results for both of them, active facilitation has gotten more detailed information and gained deeper insights, but lacked the sense of agency.

Challenge 2

Arranging time with stakeholders was our biggest challenge for the workshops. We tried to gather all librarians together to open communication between library departments, but it was impossible to summon them all at the same time. Thankfully, maintaining interest was not an issue, but it was still difficult to find a common time to gather everyone.

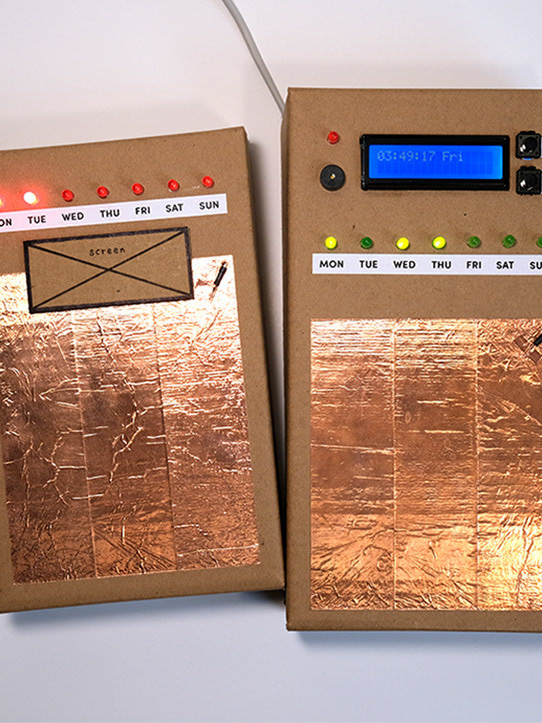

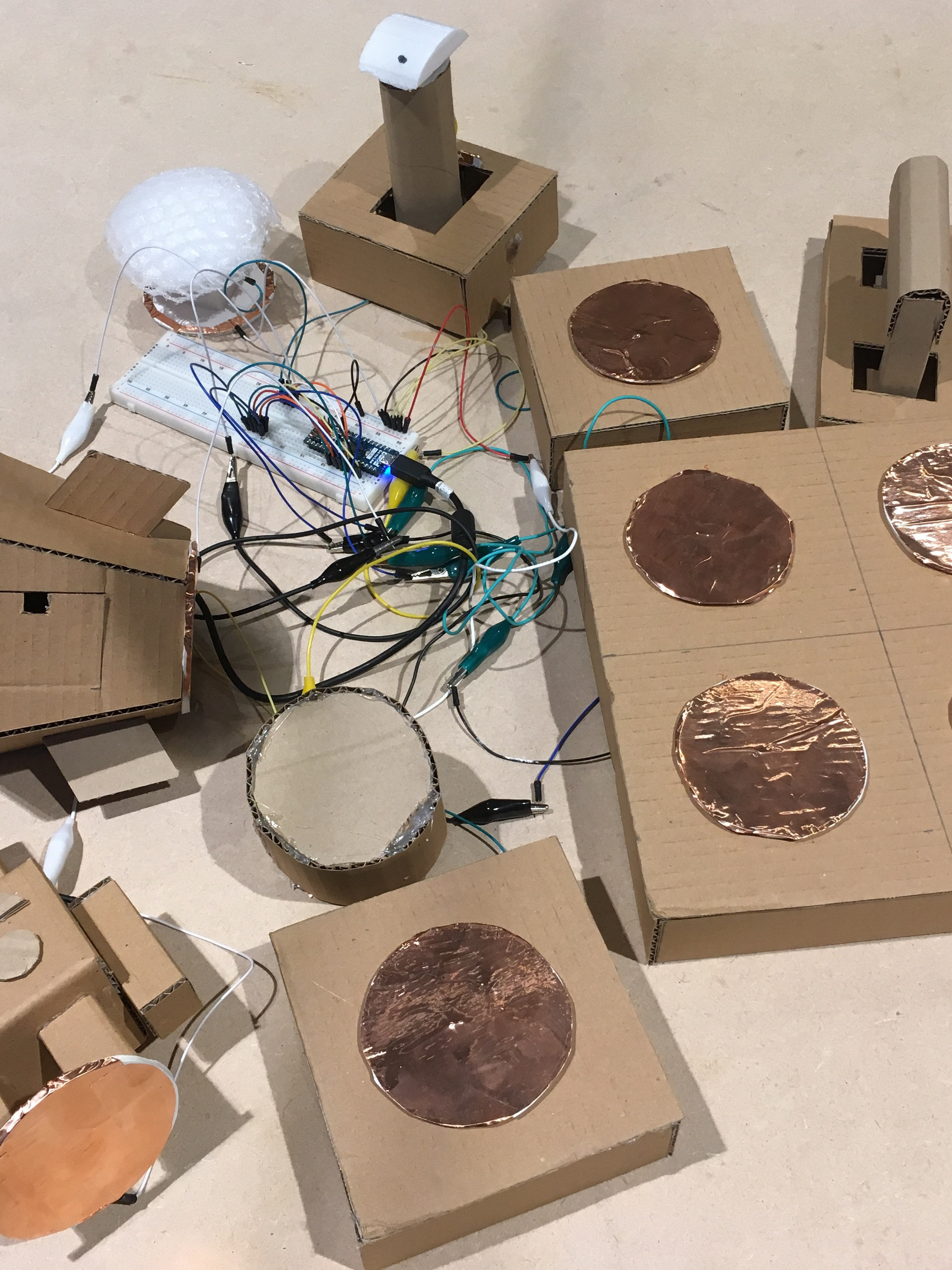

As an alternative, we have build our design game so they can participate individually and have chance to return to see what others have done and exchange feedbacks. We built our design game on Miro board, which is a collaborative digital workspace. There are benefits and drawbacks with both digital and analogue materials. The analogue materials provide tactile experience that increases the sense of ownership but it is inconvenient to carry around while working on the floor. On the other hand, the digital material makes it convenient for people to leave feedback on each other during and after the workshop.

Challenge 3

Another challenge that we faced was engaging participants to leave feedback on each other. We tried encouraging them to complete the feedback during the workshop, but they silently refused. So we decided to re-visit one of the library staff in person, and he commented that he did not want to appear critical towards his coworkers. After a couple of reminders, we provided an option to send feedbacks privately via email. This helped us to hear back from 3 library staffs and 1 did not replied. Additionally, I got the impression that they felt uncomfortable using the Miro alone.

Learnings & Outcomes

For this project, I discussed methodology choices we made and how we performed them by demonstrating participatory design that “attempts to involve those who will become the ‘users’ throughout the design development process” as co-creators (Sanders & Stappers, 2012, p.19). Throughout the process, I had doubts of not knowing if our design game would generate useful insights and felt insecure about wasting participants’ time. However, I learned that the process “involved surrender by all, including the designers, to allow things to happen and not to predict a specific outcome” (Light & Akama, 2012, p.67). Our process was messy and far from linear. There has been constant revisions and we were often lost. Nonetheless, we learned to trust the process and experienced the strength of co-design as a way to keep our design relevant and grounded.

As an outcome, we have articulated a desirable, viable, and feasible vision for the Malmö City Library.

Acknowledgement

I thank librarians and library assistants from Malmö City Library – Nina, Mimmi, Madde, Lisa, Sus, and Omar – for their participation and contribution.

References

Light, A & Akama, Y., (2012). The Human Touch: Participatory practice and the role of facilitation in designing with communities. PDC '12: Proceedings of the 12th Participatory Design Conference, 1, 61-70.

Penin, L., Staszowski, E., Bruce, J., Adams, B., & Amatulllo, M. (2019). Public Libraries as Engines of Democracy: A research and pedagogical case study on design for re-entry. NORDES, 8, 1-10.

Sanders, E. & Stappers, P. (2012). Convivial Toolbox. BIS Publishers.

Stickdorn, M., Hormess M. E., Lawrence, A., & Schneider, J. (2018). This Is Service Design Doing. O'Reilly Media, Inc.